mississippi

olivia y. v. governor reeves

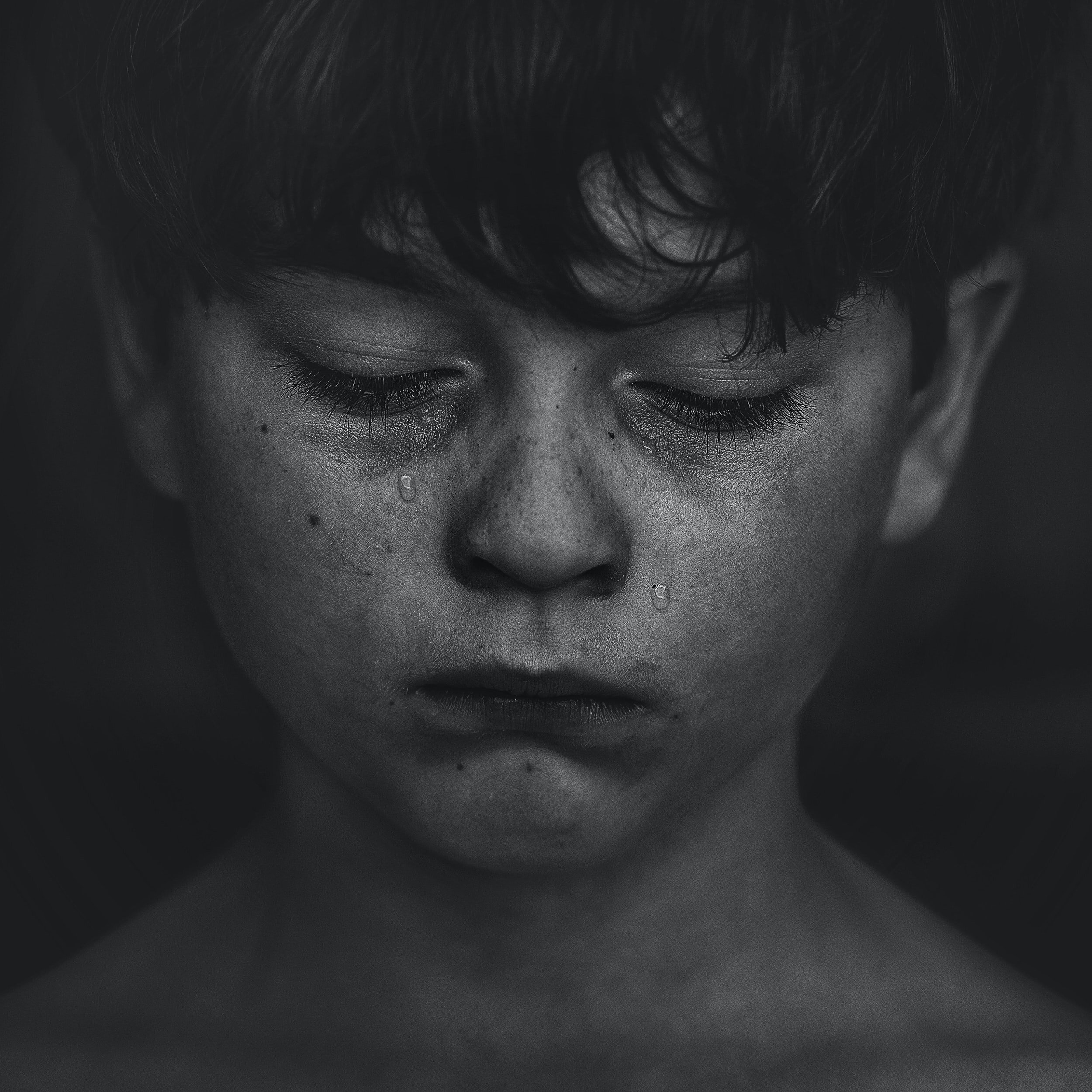

Plaintiffs: 13 foster children, aged 2 through 17 years old, representing the class of over 8,000 Mississippi foster children

Read the amended complaint here (filed May 7, 2004).

about the Mississippi Foster care system

As of September 30, 2019, there were 4,200 children in Mississippi state custody.

Since 2014, at least five children died in foster homes that Mississippi’s Department of Family and Children’s Services (DFCS) had been monitoring.

A court-ordered report documented that in 2012 Mississippi spent less on child welfare per foster child than every state but Nevada.

Mississippi’s DFCS has a history of placing many children who come into foster care in homes with relatives, without doing adequate investigations of whether the homes are safe or able to care for the children and whether the homes meet licensing standards. As of 2016, Mississippi had over 500 children in unlicensed foster care placements.

DFCS often fails to investigate or substantiate reported abuse and neglect, or provide services, even when confronted with strong evidence of children being in harm’s way.

The state admits that it does not have sufficient caseworkers to provide full assessments of children’s safety or to fulfill its obligations to children in foster care. The state also admits its continued noncompliance with court-ordered reforms.

allegations

Mississippi has been continuously out of compliance with the 2008 court order to address its long-standing systemic deficiencies. The court-appointed Monitor has documented widespread noncompliance in such areas as accuracy of data; unmanageable worker caseloads; failure to visit children and families; placement of children in unqualified, unlicensed facilities; and failure to provide basic health care. The children in custody or under Mississippi’s ongoing supervision suffer from maltreatment and abuse. In several cases, children have died needlessly. Mississippi has acknowledged its systemic failings, but had continued to intentionally and arbitrarily deny abused and neglected children access to the benefits of a constitutional child welfare system, and of a federal court order to protect them from emotional and physical injury.

advocacy goals

There is no question that Mississippi has one of the worst child welfare records in the country. In the absence of any evidence to indicate the state has either the capacity or will to do better, Plaintiffs brought a contempt motion against the state in March 2015, asking the Court to put this system under the control of a federal receiver. After Plaintiffs filed their contempt motion, the state admitted noncompliance and an ongoing lack of current capacity. After a restructuring of the child welfare system, the state once again promised reform but a new administration then asked the federal court to relieve it of a key obligation - to hire a sufficient number of caseworkers. Since that time, the Monitor has issued two reports finding the state was out of compliance, or without the necessary data to document compliance with about two-thirds of the required 113 requirements of the court order.

progress

Mississippi continues to acknowledge its systemic failure to guarantee children in foster care their constitutional rights. During 2017 monitoring was suspended and the state spent its time building its capacity to come into compliance with a renegotiated settlement agreement. The state worked with Public Catalyst, an independent consulting group, to help address the many systemic failings in the structure of its child protective system. The child welfare agency separated from the larger Department of Human Services, so that it could function more efficiently and so that its commissioner would report directly to the governor. The state’s management team worked on addressing specific shortcomings in a range of activities: hiring to meet caseload goals, instituting a new approach to licensing and addressing the backlog in unlicensed homes, and beginning the process of creating a functional redesign of the computer information system. Public Catalyst, which formally began to monitor the state’s activities in 2018 and its compliance with the new settlement agreement, has filed two reports documenting the state’s continuing non-compliance.

In 2021, after a new commissioner had been appointed to head the agency, and a new federal judge had been appointed to handle the case, the state finally asked for a “rebuilding period,” acknowledging that it could not meet the commitments in the court order. The commissioner has made commitments to deliver on specific requirements in the settlement agreement, including increasing workers and taking other steps to ensure the safety of the children in the system. That “rebuilding period” ends in 2023, the commissioner will be reporting regularly on the progress that is being made, and the court-appointed monitor will be working with the state to both improve its data system and to build the agency’s capacity. At the end of the period, we hope this commitment will have resulted in a stronger, safer child welfare system or we will return to court with all the data necessary to prove that the federal court has to take over the system.

meet our plaintiffs

(All names below are pseudonyms)

olivia

Olivia was a three-and-a-half-year-old girl when the complaint was filed, who entered DFCS custody weighing a mere 22 pounds because her mother had severely neglected and malnourished her. Within three months in the state’s custody, DFCS repeatedly uprooted her, moving her through five separate placements. In one placement, a convicted rapist lived in the house. DFCS failed to recognize that Olivia was in need of medical attention from the start, instead labeling her “cute” and “petite.” Her health worsened while in DFCS custody. Months after she entered the child welfare system, Olivia finally received a medical examination that showed signs of malnourishment, depression, developmental delays, and sexual abuse.

jamison

Jamison was a 17-year-old boy at the time of filing, whose mother abused him and who has been in DFCS custody for more than 12 years. He has been shuffled through at least 28 placements. Many of these placements had inadequate resources to meet his needs. Although in some instances loving foster homes wanted to adopt him, DFCS never took the necessary steps to make these living situations permanent. Instead, DFCS inappropriately chose to send Jamison back to his abusive biological mother. That placement was traumatic. Jamison witnessed a two-year-old boy living in the house being thrown into walls, beaten with an iron belt, and eventually killed by an adult in the residence. He also witnessed his mother’s boyfriends beat her repeatedly. At one point, DFCS also sent Jamison to live with his out-of-state father, who had lost parental rights due to criminal activity, and despite the home not receiving certification from the other state. Jamison is a bright and motivated student who has not been allowed to attend regular public high school, instead being shunted to G.E.D. classes. Jamison desperately wants to receive his high school diploma and apply to four-year colleges out of state. DFCS workers have told him to give up on these dreams and that his options are community college or job corps.

desiree, renee, tyson + monique

Desiree, Renee, Tyson, and Monique are a sibling group of three girls and one boy, aged nine, six, five and two and a half at the time of the complaint. These four children had been homeless and neglected because their mother refused to care for them. Instead of referring the case to Youth Court, as required by law, DFCS asked their septuagenarian great-grandmother to take them. The woman was already caring for six other children, some of whom were siblings of the plaintiff children. Despite the great-grandmother living on a fixed income, DFCS told her there was no possibility of financial help or becoming a foster parent. The great-grandmother suffered a stroke only months after the plaintiff children arrived in her home, and the biological mother returned and removed the plaintiff children and her other children. DFCS is aware that the plaintiff children were residing with their mother with no stable housing, but the agency refused to take action to protect the children.

Mississippi has been continuously out of compliance with the 2008 court order to address its long-standing systemic deficiencies. The court-appointed monitor has documented widespread noncompliance in such areas as accuracy of data, unmanageable worker caseloads, failure to visit children and families, placement of children in unqualified, unlicensed facilities, and failure to provide basic health care.

The children in custody or on Mississippi’s monitoring list suffer from maltreatment and abuse.